Sonnambula

A Bellini Gem in a New Zimmerman Setting

New York

Presenting Bellini's "La Sonnambula" (1831) as a backstage drama, as Mary Zimmerman did in the new production at the Metropolitan Opera, turned out to be a pretty clever way to reconcile the flimsy plot and deep emotional content of this bel canto gem. By setting it in an airy, windowed rehearsal room (Daniel Ostling designed the handsome space) rather than the usual kitschy Swiss village, and having the principals and chorus be singers rehearsing their roles in the opera while living some of its events, Ms. Zimmerman played with the idea of performance and reality. What goes into creating a character? How much emotion is real, and how much is manufactured? With the artifice of the final artistic product stripped out for much of the performance, the two main singers were also able to build their central drama in a direct and engaging way.

Those two, Amina (Natalie Dessay) and Elvino (Juan Diego Florez), are planning to be married. Their village is haunted by a ghost. A mysterious aristocratic stranger turns up, making Elvino jealous, and when Amina sleepwalks (she's the ghost) and ends up in the count's bed, Elvino dumps her. Happily, the truth is revealed in Act II, and the lovers are reunited.

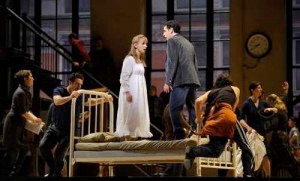

Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera

Juan Diego Florez and Natalie Dessay in the Metropolitan Opera

This production added an extra layer of cynicism: Ms. Dessay made her entrance while swathed in a white coat, chatting on a cell phone, and ignoring the admiring chorus. Her diva act continued through her first aria, as she tried on costume shoes and imperiously rejected all the wigs while singing high roulades. But she soon slipped into the character of the virtuous and misunderstood Amina, to the extent that in her "real life moments" -- as when Elvino gave her a ring during a rehearsal pause -- she displayed Amina's vulnerability. By the time her Act II sleepwalking aria came around -- she walked in through a window from outside and wrote "Aria" on a blackboard first -- the deliberate distancing effect of that gesture lasted only for a moment, and the identification seemed complete.

The concept also gave the director more choices about how to use the chorus, which is onstage much of the time -- its members could review their scores, rehearse their own bits, and clandestinely watch the lovers' progress. Sometimes the chorus's activities became distracting: In the Act I finale, as Elvino rejected Amina, everyone started ripping up paper and manically tossing it around the stage. But on balance, the concept worked. Watching the Act II finale, with everyone fully costumed in bright dirndls and the lighting illuminating the full color palette of the stage -- very different from the deliberately monochromatic visual tone of rest of the show -- one remembered the pieces that made up the final product. (Mara Blumenfeld did the costumes, T.J. Gerckens the lighting.)

Best of all was the remarkable intimacy of the vocal performances by Ms. Dessay and Mr. Florez. Their onstage chemistry is terrific, and the vocal blend of these two light, agile, yet colorful voices was very beautiful, more noticeable in this opera than in the purely comic "La Fille du Regiment," their previous pairing at the Met. They played their roles like real lovers, both in the happy moments, when their soft singing and intense focus drew the audience closer to them rather than wowing us with display, and in their tragic ones. The display was there as well, of course. Both navigated their ornamentation with great flair. Ms. Dessay used it seamlessly for character effect and Mr. Florez's secure, effortless high notes and suave approach remain a marvel.

Bass Michele Pertusi played Count Rodolfo as a real wolf, with his eye on a pretty girl, but he was hilariously disconcerted when she showed up in his room. Solid contributions came from Jennifer Black as Lisa, who wants Elvino for herself (she's the village innkeeper, but also the stage manager of the show); Jeremy Galyon as Lisa's importunate suitor; and Jane Bunnell as Amina's devoted, fur-clad stage mother.

The chorus sang well, creating a lively frame for the central action, and played its part as the sympathetic observer very well; dancers, choreographed by Daniel Pelzig, also animated the show. Only Evelino Pidò's conducting was pedestrian. He was the weak link -- not the production team, which was greeted by unwarranted boos from the audience at the curtain call.

Bellini, La Sonnambula at the Met with Dessay, Flórez, and Pertusi, dir. Zimmerman

Natalie Dessay and Juan Diego Flórez argue in Bellini's La Sonnambula at the Met

Metropolitan Opera House

March 14, 2009

An immense success in its first production in 1831 as well as in its first performances at the Met (1883), La Sonnambula's popularity waned—at the Met at least—after the First World War. In later revivals, it was presented as a vehicle for sopranos who could fully exploit the florid ornament of Bellini's writing for its heroine, Amina. Twenty-eight years elapsed between Lily Pons' last performance of the role in 1935 and Joan Sutherland's first appearance in it in 1963, which was hailed as the revival of the lost art of bel canto. It held its own at the Met as long as Sutherland performed it, that is, until 1969. Three years later Renata Scotto brought a more dramatic approach to Amina, but her performances of the role never went beyond the 1972 season. Only this year, 37 years later, has the opera been revived, with Natalie Dessay, who enters the role with her own mélange of satisfying musicality, dramatic energy, and charismatic charm, in an unconventional production by Mary Zimmerman, which has attracted a storm of vociferous criticism.

La Sonnambula's original success depended on a careful balance of specific circumstances—estimation of the competition, choice of genre and subject, the writing of the principle parts for the most admired soloists of the time; and the collaboration between Bellini, his backers, the librettist Romani, with whom he had worked many times before, and the singers was extremely close—similar to the way musical commissions are carried out today, but focused on commercial success. In 1831 Bellini had been working on an Ernani after Victor Hugo, but, knowing that Donizetti was about to stage an Anna Bolena, he decided not to confront his competitor head on with another grand tragedy, but to take up a lighter genre, an opera semiseria, based on a successful ballet of 1827, La Somnambule.

Romani changed the setting from Provence to a Swiss village, a locality familiar to wealthy tourists and admirers of Rossini, who had recently closed his career with a Swiss historical subject. It tells the story of simple villagers, Amina and Elvino, who are about to get married. Their life conveniently revolves around the local inn, where the celebrations are to take place. The innkeeper, Lisa, has previously been engaged to Elvino, and is the only person among the villagers who is not filled with admiration for Amina's beauty and virtue. A mysterious traveller, Rodolfo, arrives and takes a room at the inn. Curiously, the village is familiar to him and conjures up pleasant memories. Lisa figures out that Rodolfo is the son of the local count. That night in his room, an intimacy begins, interrupted by Amina, who is walking in her sleep. Lisa hides in the closet, dropping her scarf, while Amina lies down on the count's bed and falls asleep. The ensuing conflict, in which Amina's virtue is compromised, the villagers accuse her, and Elvino cancels the marriage. Of course none of these people know about sleepwalking. Lisa takes advantage of the situation and renews her engagement to Elvino. Poor Amina is miserable. The next day the villagers realize that they acted in haste and approach Rodolfo, who confirms Amina's innocence. At first Elvino refuses to pay attention, but Amina reappears, sleepwalking, singing about her distress and dreaming of her marriage to Elvino. Lisa's deception is exposed, and Amina is vindicated. The opera concludes with a joyful chorus anticipating the nuptials which were to have occurred at the beginning.

Of course stories about complications in the lives of simple people are as popular today as they were in the Romantic period, although, perhaps, not in opera, and then more in terms of Porgy and Bess, Wozzeck and Marie, Tony and Maria, or George and Lennie, rather than Swiss villagers in their tidy peasant costumes. For tourists in Switzerland the village inn has long been replaced by slick, highly professionalized hotels. What traveller today lounges about the village inn or strolls its streets? How to present La Sonnambula without choking the audience with Swiss kitsch and nostalgia for things long beyond the memory, let alone the experience of most people? (Remember that La Sonnambula has reappeared only when there was a soprano who could bring off Amina.)

Mary Zimmerman is well aware of all this and has decided to present the opera as a backstage musical, or a rehearsal for a production of the opera, in which the participants experience the same relationships and and entanglements as the characters they perform. This is of course not a terribly original idea in itself, and the complications of the added layer did not exactly reinforce the clarity of the of the story. Still, I thought it made for an entertaining show, and I especially enjoyed Zimmerman's hommage to the great Jean Vigo's Zéro de Conduite. Daniel Ostling's handsome set, T. J. Gerckens's glowing lighting, Daniel Pelzig's choreography, and the impeccable, even virtuosic execution of extremely complex scenes made it all the more accessible, if not entirely convincing. I was aided in this by avoiding reading her essay about the production until after the performance was over. When I finally did read this somewhat doughy and occasionally obscure bit of prose, I began to like the production less. There was just enough preening in it and just enough condescension to put me on my guard. Do we need all this sophistication in La Sonnambula, when what we're really interested in is the vulnerability of the characters (Amina's above all.), their transient emotions, and Bellini's delightful music? Of course not...and all that stage business was more of a distraction from those simple relationships and emotions than an expansion of them.

I have to confess that most of my energy went into listening rather than watching and interpreting. Evelino Pidò produced clean, energetic, and expressive playing from the Met Orchestra, a sparkling accompaniment for a consistently admirable cast of singers. Like this season's production of Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor, La Sonnambula enjoyed the benefits of the felicitous technical and dramatic approach to bel canto opera which has evolved over the past sixty years. Singers and conductors, balancing and merging the styles of Callas and Sutherland, know how to bring out the dramatic and emotive core of the pretty melodies and the impressive ornament. Singers like Netrebko, Beczała, Dessay, and Flórez can all elicit a moving expressivity in both the straightforwardly melodic and the virtuosic elements of their parts. Natalie Dessay is more a Callas than a Sutherland, if of a more cheerful, extraverted sort. Showmanship, a virtuosity on her own terms, and genuine dramatic perception give her an exceptional authority in this music today, but at the Met she is not its only exponent. I think we are fortunate that we can simply listen, admire, and be moved by bel canto opera, rather than perceiving it as a lost art revived by a Verdian transfusion or a meticulously reconstructed technical specialism. Juan Diego Flórez addressed Elvino with a very light, bright, but mellow tenor and a fine sense of style. Jane Bunnell offered a vivid and variegated Teresa, and Jennifer Black brought nuance and depth to the villainess Lisa, who was in this production, mind you, both an innkeeper and a stage director. Bass Michele Pertusi sang Rodolfo with wit and elegance, projecting just the right désinvolture as a slightly spoiled aristocrat who is fundamentally a decent fellow.

I left the Met's new production of La Sonnambula in high spirits after a musically impeccable and dramatically interesting evening. Mary Zimmerman may have labored a bit too earnestly on it, but she also knows how to have fun, and that, I believe, saved her part of the show in the end. The musicians needed no apologies.